China 中国

TIME

I completely reject the linear conceptualisation of time. I don’t think any of us experience time as a succession of moments but rather as drips and deluges. Sometimes nothing happens for years, then everything happens at once. Some moments you never really leave at all. Others are like depth charges that glide by at the time but hit you like a hurricane years later.

Katie, on the other hand, has an amazing mind for linear time. She knows where she was and what she was doing at any given month going back years. She’s also very good at anniversaries, and when I mentioned to her that I can’t get China out of my head lately she reminded me that it’s been exactly ten years this year since I left.

I’ve been missing the place acutely. Actually, not just the place but the _feel_ of the place. I miss the sticky Shanghai air on my skin. It’s a tangible, tactile thing. I can’t get that air back. It probably doesn’t even exist anymore. But I can go back to the photographs I took there (which were actually the first photographs I ever took). So for the next while I’m going to be doing that, posting a few nostalgia pics and writing what I remember about that very strange and wonderful time and place.

PLANTS

I estimate I use about 200 Chinese medicinal herbs in my practice at the moment. I’ve been told a master herbalist uses about 600. A hospital pharmacy will stock 800. The Brion Institute database stores 2,000.

Plants are like air. You don’t, or at least I didn’t, realise the properties of the plants that surround you until they change. Irish grass is _rich_. It’s luxurious. It’s thick, deep green, swollen with moisture. It cushions and rebounds and stains your clothes. The grass in Shanghai is tough, fibrous. It’s dry, growing in defensive clumps . There are patches of hard dry soil in between each outpost. Of course across all varied biomes of China are every possible manifestation of grass but the same way the air above me changed in Shanghai, so did the grass beneath me.

The plants in the cities of China are survivors, and opportunists. The same way the grass grows from patches of earth at the edge of intersections so too do people grow vegetables in the narrow strips of soil in the middle of dual carriageways. I think there might even be a mutual appreciation there. I heard stories of young men training in kung fu / gong fu that would go to the city parks and ‘find the right tree’ for them, banging, stretching and scraping their bodies against it to relieve their training aches and pains. Bamboo is turned into rafts, ladders, scaffolding, literature, food, medicine, metaphor. It’s woven into the fabric of life and society, and can be a map for connecting with that life and society too.

SPACE

When I was a kid I used to set off early in the morning with my terrier and be gone exploring the fields around until evening. There was a dense thicket of brambles spilling over a dry stone wall that I tore at for hours until I could force my way inside. There I could sit on the bare earth between the trunks, head bowed beneath the thorns, safe in my secret place no one else could enter.

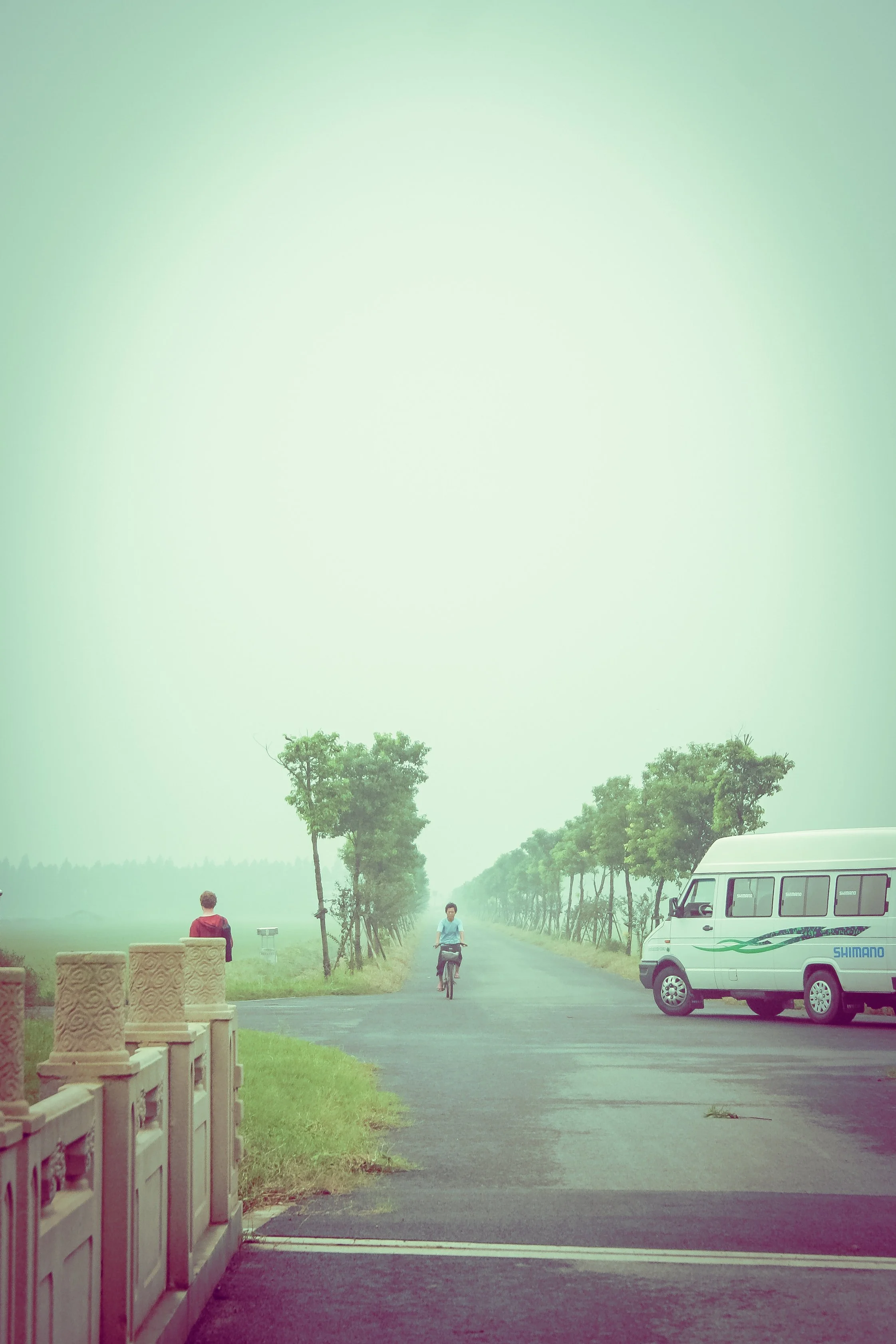

Shanghai has an estimated 30 million people and is decidedly short on secret thickets. I nearly lost my mind the first few weeks. A walk around the streets at 3am would still assault me with music, cigarettes, conversation, steam, taxis, stinky tofu. I could find no moment of space, silence or stillness for myself. So I started looking for it in other people. Every time I saw anybody in the city being still, or quiet I observed, and usually photographed them. The ability of people to find moments of placidity amidst the chaos fascinated me.

There’s a story about the Bodhisattvas someone once told me, that they would seek out the most difficult environments in order to look for peace there. He said that they would go to battlefields, cover themselves in the ash of the burning bodies and pray for the souls there to be released. I don’t know whether the peace of the Shanghai placid-nauts happened consciously, or randomly, or whether it was just a natural human reaction to so much of its opposite. But eventually it sunk in that even amidst the most determined chaos there are _always_ moments of peace. Something about that knowledge transmuted my relationship to the city. Chaos became life, and to some small extent, I became part of that.

A bit. I still like my peace.

RIVER

Every day after clinic and class were finished I would take my electric scooter to the river. The ride started slow, over the speed bumps, hard left onto the busy road, taking it nice and handy until I reached the water’s edge. Then I could floor it, head down, the thick evening air flowing past me like syrup, a constant ‘..phut…phut…phut…’ of insects smacking off my helmet. One time on a particularly late ride home a bat did the same thing and almost concussed me.

Hangzhou is split in two by the Qiantang River and during the day it is a fearsome natural barrier. The traffic in the city is extraordinary and picking the wrong bridge at the wrong time could see you stuck for two hours or more. But at night it gives back. The soil is fertile near its banks and crops are planted right up to the water’s edge. Nearby there are primary schools and universities and so the crowd is comprised of children, laughing 20 year olds and doting grandparents. On my joyous days these figures whipped by in a slideshow of smiling faces. On my more pensive nights I went on foot later and absorbed the quiet murmured conversations of people who were doing much the same as me; counting on the river to give clarity and peace.

On one of my first weeks there one of my teachers invited me to a… thing. My broken Mandarin didn’t allow me to understand fully what I was signing up for but if I let that stop me agreeing to things I would never had done anything. Along the wide deserted streets and through the winding, lightless farmers’ fields streamed hundreds of people. We reached the water’s edge and stood there, waiting. Then the sky exploded, a fireworks display like I’d never even imagined, doubled in the waters of the Qiantang. I usually walked the river by myself and it felt good to be part of a group there.

Months later I stopped by the riverside to watch a man set off his own single, blinding firework, get back into his car and drive away, leaving just the smoke of his flare floating in the air. A personal act of offering, or celebration, or catharsis.

FIRE

I thought I knew what fireworks were. One year at the Rose of Tralee myself and the family went to the town park and watched a few decorous pops of light illuminate the shrubs. Families murmured and clapped politely. It was nice.

Fireworks in China are pure adrenaline. Their job is to remind you that life is chaos and violence and one day the Sun will consume the Earth. During Spring Festival / Chun Jie they occur at any time, at any place, usually no more than 3 metres away from your face. Going for an early morning bubble tea? Fireworks. Waiting for your taxi at the intersection? Fireworks. Hanging out laundry on your balcony? Fireworks. This is made even more eerie by the fact that for the three weeks of Chinese New Year almost nothing is open. You walk around deserted streets void of traffic, pacing by empty shops and restaurants, the cacophony of city life completely stilled. Except for the constant explosions.

This combination of quiet city and violent bursts gives a kind of echolocation effect. You start to feel the city in your teeth and eardrums, the echoed sound of an alley as opposed to a broad street, of an overpass as opposed to a housing estate. They each have their own sonic signature.

I never got used to the fireworks. They always made my heart pound, made me hunch my shoulders and clench my jaw. I’m not sure I wanted to get used to them. I have a deep-rooted belief that if something is exploding nearby that you should probably pay attention to that. But it was a good reminder that you don’t need to enjoy, or adapt, or accept everything about a place to enjoy it.